A History Lesson

I feel fortunate in many ways for having had the opportunity to be a part of and live through over 50 years of significant dollar related economic history.

This due to the fact that I started trading as a member of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange on July 15, 1970. That allowed me to evolve from being a cattle, hog, and pork belly trader in 1970 to later in the late 1990’s managing Asian based currency funds and being a part of the huge change induced by futures market trading of the dollar, Treasuries, and Gold futures markets on the CME. Leo Melamed of the CME, as Chairman of the CME at that time, and through concepts brought forward by Milton Friedman, was someone all of us traders knew well as he brought us into a new world.

Some of this history in reflected in the Bloomberg Article written by John Authers and published today 8/15/21. I think it is excellent and provides a lot of background to factors that could unfold in coming market events.

“Prosperity without war requires action on three fronts,” President Richard Nixon told America in a televised address 50 years ago today. “We must create more and better jobs; we must stop the rise in the cost of living; we must protect the dollar from the attacks of international money speculators.”

Then he administered what is now known as the “Nixon Shock”: He closed the “gold window.” Under the Bretton Woods Agreement, sealed at a hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944, the U.S. promised to convert into gold any dollars brought by other countries’ central banks at a rate of $35 per ounce. Other currencies traded at fixed exchange rates to the dollar. In effect, the entire Western financial system was pegged to gold, via the dollar.

No more, Nixon announced. Henceforward, the dollar would be worth whatever people thought it was worth. He meant this as a temporary measure. Gold was flowing out of the U.S. as the war’s defeated countries re-emerged as economic competitors. Other countries had to let the dollar drop a little. Closing the gold window for a while would show that Nixon was serious.

Read More: 50 Years After Going Off Gold, the Dollar Must Go for Crypto

But as it turned out, the gold standard was over. Months of frantic diplomacy by Paul Volcker, the future Federal Reserve chairman, yielded a 10-country agreement on a new system of fixed rates at a new gold price, but this soon collapsed, and nothing replaced it. Rather than adjust Bretton Woods as he intended, Nixon ushered in 50 years of fiat currencies, backed only by confidence in the issuing governments and central banks.

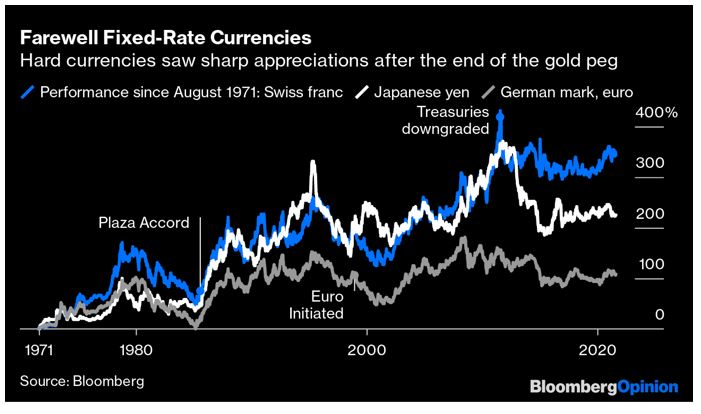

Also unwittingly, Nixon ended fixed exchange rates. Flexible rates have been the norm ever since, putting all currencies at the mercy of the “international money speculators” whom Nixon excoriated. Free markets in currencies, commodities and debt have flourished in a way unimaginable under Bretton Woods.

The U.S., along with much of the rest of the world, has largely enjoyed 50 years of the “prosperity without war” Nixon promised, albeit with increasing inequality in the developed world. But the anniversary arrives amid great apprehension. In the wake of the pandemic, inflation has spiked higher. The global financial system has never found a replacement for gold, and currently rests on minimal interest rates and, in turn, on the presumption that inflation has been definitively slayed, even without the discipline of a gold standard. If the pandemic drives up inflation, that could administer a shock to rival Nixon’s. A number of standards have risen to replace gold over the past half-century, and have ended in crisis. What might happen if the world now loses faith in central banks’ ability to control inflation is alarming to contemplate.

| America’s Role in the World |

Nixon may have appeared to abdicate American leadership, but losing the gold peg has made the U.S even more central to global finance than it was in 1971. Liaquat Ahamed, author of “Lords of Finance,” which tells the story of the disastrous moves on and off the gold standard between the world wars, said: “The centrality of the U.S. dollar as the world’s currency of denomination for trade and capital markets actually was helped by 1971. It eliminated a constraint on U.S. fiscal and monetary policy. The liberalization of capital markets after 1971 actually was a giant boon for the U.S. financial system and U.S. financial firms because there was no alternative.”

The Fed remains the world’s most powerful financial institution. The one truly global financial crisis, in 2008, was made in America, and it was only the Fed’s swap lines that saved a number of large emerging markets from incipient disaster. Twice, an aggressive tightening of interest rates in the U.S. — by Paul Volcker in the early 1980s and by Alan Greenspan in 1994 — attracted money to the U.S., pushed up the dollar, and wrought havoc in emerging markets that had borrowed heavily in dollars.

Wall Street also grew more powerful, aided by radical deregulation in the three decades after 1971. Bankers from the “money center” banks that had dealt with Wall Street panics before the creation of the Fed popped up as essential ambassadors in debt crises from Latin America to the Pacific Rim.

The 10-year Treasury yield is entrenched as the world’s “risk-free” benchmark for transactions. Even after U.S. sovereign debt was downgraded from AAA to AA+ by Standard & Poor’s in 2011, the response of international investors was to run for safety — in Treasuries. They see no alternative.

According to MSCI, the global indexing group, the U.S. stock market’s share of total global market capitalization, at 59.6%, is as high as it was in 1971, despite far faster growth in the emerging world since then. The dollar itself is still involved in a remarkable 88% of all foreign exchange transactions, according to the Bank of International Settlements.

Some argue that 1971’s other Nixon Shock, Henry Kissinger’s visit to Chairman Mao Zedong, did more to reduce America’s role in the world, but that is tenuous. The great Chinese growth story was decades away when Nixon made his diplomatic opening. Only after Mao’s death, Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre, and accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 did China’s economic miracle take shape. China is altering America’s role in the world now, but the end of Bretton Woods has little to do with it.

Arguably, Nixon’s coup was just a recognition that the U.S. had completed its post-war task of overseeing global recovery. Bretton Woods was designed primarily by John Maynard Keynes, who called the gold standard a “barbarous relic.” His rules were designed to avoid the tragic mistakes that followed the First World War. That meant fixed rates with some give in them, and a central position for the world’s preeminent financial power to police the post-war rebuilding project. Gold bolstered confidence that there could be no repeat of Weimar Germany’s hyper-inflation. By 1971, the Japanese and German economic miracles had happened. America’s job was done.

Nixon ended a Keynesian system that made the world safe for the Keynesianism of the 1950s and 1960s. And, all unknowingly, he ushered in a free market order built on the principles of Milton Friedman.

| The Rise of Markets |

Friedman, growing in influence in the 1960s, claimed that Bretton Woods “practically insures the maximum of destabilizing speculation.” He wanted to do away with government involvement and allow markets to reconcile international imbalances through freely floating exchange rates. As Volcker put it, Friedman wanted to “leave currencies to the whim of the (in his view, perfectly rational) market, without any concern for other countries’ wishes.”

Friedman was dismissed by most of the people around Nixon, but international markets were emerging even under the gold peg. Dollars poured into the then exciting growth markets of Europe. By “dithering” for years over the gold peg, says David Mulford of the Hoover Institution, the U.S. “actually helped expand and deepen the fledgling, unregulated Euro markets” and “inadvertently laid the foundation for the modern, sophisticated, truly global financial markets of today.”

Entrepreneurial Americans spied opportunities. In early 1971, Leo Melamed of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, a forum for trading agricultural products, proposed new futures in foreign exchange rates. “The idea,” Melamed said, “prompted a prominent New York banker to laughingly say that ‘foreign exchange couldn’t be entrusted to a bunch of pork belly crapshooters in Chicago.’”

Yet in early 1972, the CME launched the International Money Market, with intellectual backing from a paper by Friedman himself. By allowing for swift and liquid risk management in foreign exchange, the CME helped make floating exchange rates a practical reality — and itself became a financial behemoth.

With money increasingly nimble, no government could defend an unrealistic exchange rate, unless it imposed controls on the flow of capital. Post-1971 financial history became a litany of governments setting a peg for their currency which the markets then broke.

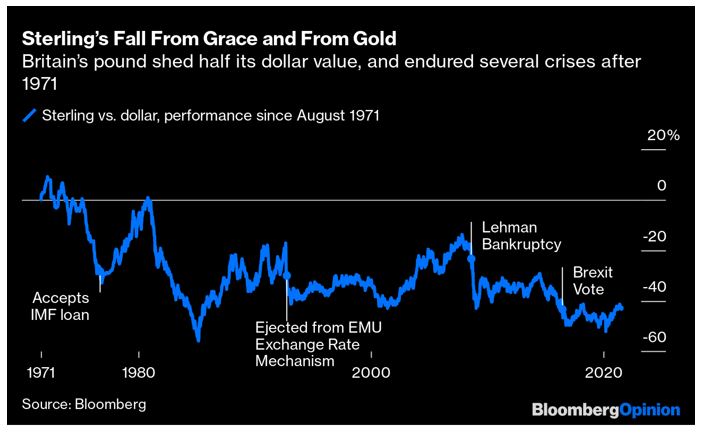

Sterling, the dollar’s predecessor as the global reserve currency, suffered serial humiliations. Already forced to devalue in 1967 under the gold peg, the pound suffered another run in 1976 that forced the U.K. to borrow from the International Monetary Fund. In 1992, it suffered ejection from the exchange rate mechanism of the European Monetary Union. George Soros (the kind of “speculator” Nixon had inveighed against in 1971) had bet that Britain could not maintain its peg to the deutschmark.

Much the same fate befell a series of emerging markets in the 1990s, from Mexico to the Asian “tiger” economies to Argentina. Just as Friedman wanted, nobody got to set anyone else’s currency.

And yet, Nixon’s abandonment of gold is widely reviled today, often by free marketeers otherwise in tune with Friedman. Free markets tend to overshoot, in both directions, and that makes economic life harder for economy ministers and entrepreneurs alike. Currencies need some kind of standard. The 50 years of fiat have seen a series of alternative, less-than-golden standards, each of which has ended in crisis.

| The Search for a New Standard |

There have been four post-gold standards, and all of them can be understood by looking at the ratio of share prices (which rise on optimism) to gold (which rises on pessimism). When the stocks-to-gold ratio is rising, confidence is high, but when it falls, there is fear of inflation.

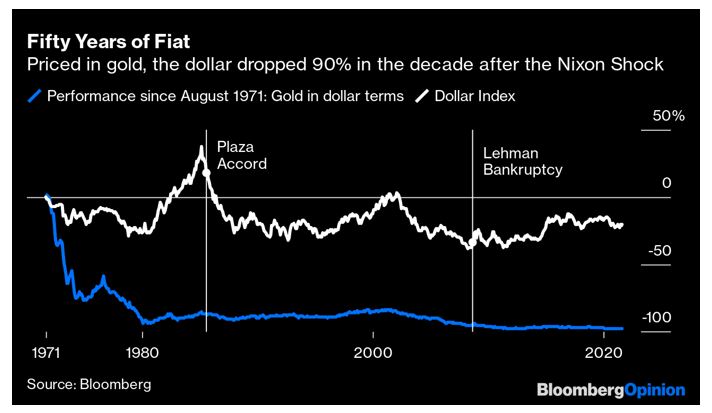

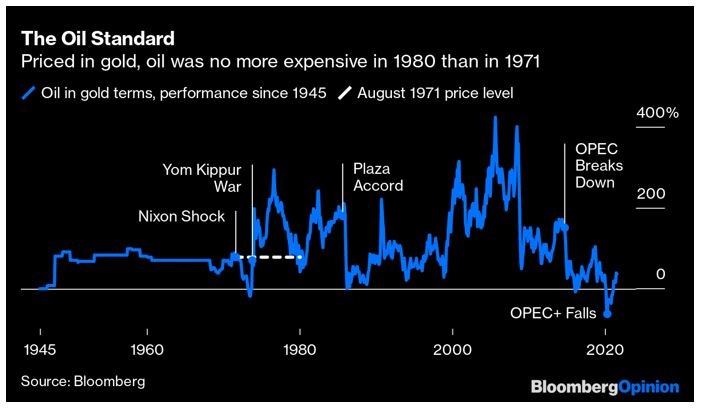

Oil Standard: Once unpegged from gold, the market delivered a savage judgment on the dollar. Its value swiftly fell by 90% in gold terms, and has never recovered. Instead, gold offered an indirect anchor through an effective oil standard. The U.S. struck a deal with Saudi Arabia to standardize all oil transactions in dollar terms. This maintained U.S. centrality, while oil exporters primed global dollar-denominated markets by recycling their “petrodollars.” The problem was that oil exporters wanted to maintain their oil’s value in terms of gold, and oil, unlike gold, is central to the industrial economy.

As Nixon’s inflationary policies eroded the dollar, oil exporters defended the oil price. Even after two oil embargoes, the oil price denominated in gold was no higher at the end of the 1970s than it had been in 1971. But those embargoes inflicted stagnation and inflation on the West.

Volcker Standard: Enter Paul Volcker. In another case of unintended consequences, President Jimmy Carter hastily installed him as Fed chairman in 1979. It proved a momentous decision. Volcker limited the supply of money, and hiked rates again and again. In doing so, he introduced an intangible standard based on a contract with the Fed to maintain the dollar’s buying power. According to Barry Eichengreen of the University of California at Berkeley, Volcker introduced “inflation targeting as an anchor for monetary policy.”

“In a way you could say that Volcker’s regime at the Fed gave the monetary system its anchor back,” says George Magnus, a professor at Oxford University and long-time foreign exchange analyst. “It’s worked pretty well.” But it came at a cost; Volcker hiked rates to 15%, provoking a second brutal recession. Just as the Bank of England had done when rejoining the gold standard after the Napoleonic wars, the Fed braved social disorder, inflicted a recession on its country — and created a trusted currency that would dominate the world for decades.

But unlike in Victorian Britain, there was no new link to gold. So how did Volcker achieve this? Painstaking empirical work by a group of economists for the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that inflation was defeated by changing psychology and not by the impact of joblessness. Differences in inflation among states with starkly different unemployment rates were minimal. But by braving unemployment, and keeping his post under Reagan, Volcker showed the world that the U.S. meant business. People no longer expected inflation, and they adjusted their behavior in what became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The Greenspan Put: Unfortunately, confidence that inflation was vanquished enabled a steady fall in bond yields that has persisted almost uninterrupted for four decades, making it ever cheaper to borrow. With no gold to limit money creation, and egged on by financial deregulation, leverage and speculation ran riot. An epic bubble finally burst in 2000.

Now, the Fed offered a new guarantee: Whatever happened, asset prices would not be allowed to fall. From 1998, when the implosion of the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund caused markets to freeze, until the collapse of Lehman Brothers 10 years later, traders noted that the central bank cut rates whenever stocks fell, and raised them only once the market was safely rising. They called this the “Greenspan Put.” The moral hazard this created fueled another wave of speculation and the financial disasters of 2008. In gold terms, stocks fell almost without interruption from 2000 to 2011. Markets were convinced that cheap money must lead to inflation.

The QE Standard: In 2011, those fears appeared to have reached the point of collapse. But instead, the fear of inflation and debasement ground to a halt, and a new regime took shape. The turning point was the rating agency Standard & Poors’ downgrade of U.S. Treasury debt from AAA to AA+. Congress and the White House were playing brinkmanship over whether the government would be allowed to borrow more, and so S&P proclaimed that the world’s risk-free security now came with risks.

This could have been the moment to end cheap credit. Instead, investors reacted as they always have in times of trouble and dived for the safe haven of Treasuries. TINA (There Is No Alternative) thinking took hold. Whatever happened, it seemed, there would always be demand for Treasuries. Subsequent massive rounds of bond purchases by the Fed (known as QE or Quantitative Easing) have rammed that message home and kept yields minimal ever since. With confidence in more money-printing by the Fed (impossible under a gold standard unless miners dig up more gold), and with plain evidence of a global stagnation in prices, investors piled into stocks, and gold tumbled into a bear market. So strong was the guarantee against inflation that central banks now actively tried to bring it back — and couldn’t.

| The Future |

Then came the pandemic. It has been hard to argue that the U.S. suffered much from the Nixon Shock. Growth from 1945 to 1971 was only slightly stronger than in the long expansion that lasted from Paul Volcker’s arrival until the financial crisis. But growth in the past QE-dominated decade has been even slower than in the stagflationary 1970s. With the pie no longer growing much, discontent over widening inequality and workers’ dwindling share — trends that started in 1971 — has become intense.

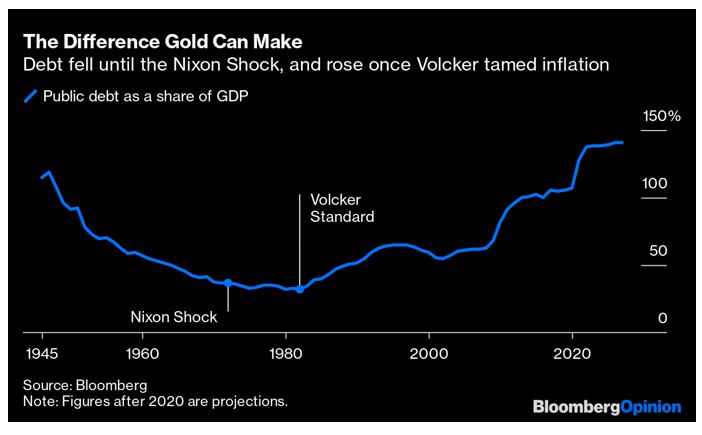

Now, the pandemic threatens to expose the impact that the lost gold discipline has had on borrowing and on government behavior. In 1945, gross federal debt was 116% of gross domestic product. By Bretton Woods’ end, the U.S had sweated this figure down to 35%. The government’s leverage dipped a little more in the 1970s: It’s hard to borrow much when inflation is rampant and rates are high. But then Volcker’s medicine took effect. By the end of 2019, on the eve of the pandemic, federal debt had ballooned to 106% of GDP, in peacetime. The pandemic will bring it to levels unseen even during war.

Until now that has been sustainable, but inflation has spiked to its highest level in decades. This may prove transitory. But if it isn’t, the TINA attitude to Treasury bonds will fail, and it is on TINA and confidence in inflation that the current system rests as surely as prior systems rested on gold.

Inflation has a way of changing people’s priorities. Nixon thought it mattered less than unemployment; after a decade of rising prices, Ronald Reagan won on a platform of beating inflation and gave Volcker the backing he needed. But what new discipline can await after the next bout of inflation? Some propose a stronger international currency or “numeraire” based around the IMF; or another attempt at managed exchange rates; or even a return to gold. Bitcoin has risen to more than $1 trillion on hopes that cryptocurrency can supplant fiat currencies — which would mean overthrowing the government monopoly over currency in favor of some form of anarcho-capitalism. All these possibilities seem far-fetched. And all would hurt.

No new “system” can replace what Volcker late in life called a “nonsystem that had prevailed for 50 years” without the world first suffering an inflationary crisis, and — as in 1944 and in 1971 — an American lead. Money knows no borders, and the chances of international agreement are zero. Nixon’s dramatic move had nothing like the consequences he intended, but he did show that if the global financial architecture is to shift, an ever more powerful America must make the first move.”

Leave a Reply