What Could go Wrong ?

Today I will continue with my long held view that John Mauldin provides one of the best analysis viewpoints in the business. He, along with John Hussman are kind of the cornerstones for my own viewpoints gathered over some 50 + years of trading. Here is John’s latest newsletter.

By John Mauldin | Sept 25, 2021

I have written several letters on the theme that the best investment posture is cautious optimism. Pessimism and bearishness never get you in the game, while untamed optimism means that at some point, you’ll have a serious setback. The cautiously optimistic investor asks both, “What could go wrong?” and “What could go right?”

Dave Portnoy notwithstanding, stock prices don’t always go up. Investors got a little reminder last week when financial media suddenly had some drama to report. Then it subsided, and the market went right back up.

The latest volatility may or may not turn into something more extended. Some of the most respected market analysts are turning bearish. Still, others expect the bull market to continue. Timing is hard. Yet nothing has happened to make bear markets impossible. Stocks are overextended by many different measurements, so at some point, the bears will take control. More than a few investors aren’t ready for that possibility.

Today, I want to show you how richly valued the market is and then review some of the top risks that could force it downward. Like those sandpiles I talk about, we don’t know exactly what will trigger a collapse. We know something will do it. Sandpiles don’t grow to infinity.

But then we’re going to ask what could go right? Sandpiles don’t grow to infinity, but they can grow a lot higher for longer than many expect.

Different scenarios suggest different strategic responses. It pays to think about what could happen. It will let you plan ahead and maybe make some decisions in advance.

Starting Price Matters

Making money in stocks is really quite simple. You buy a stock and then sell it at a higher price. That means two things need to happen.

- The stock price rises above your purchase price.

- You sell while it is up there.

This is why your starting (buy) price matters. The higher it is, the fewer chances you have to sell at a profit. Buying a stock whose price is already extreme puts the odds against you. That’s what people have been doing, and, to be fair, it’s worked well for many. But the jury is still out on that because most of those folks haven’t yet sold.

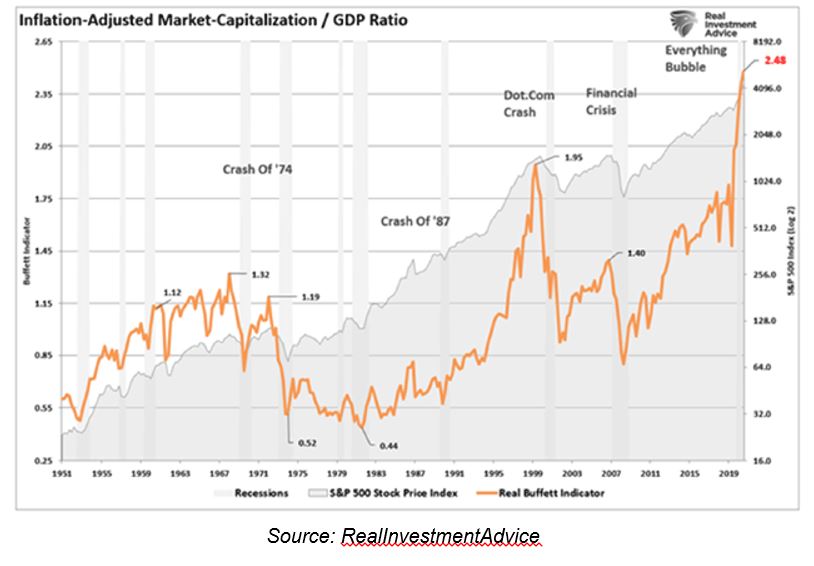

The so-called “Buffett Indicator” is one of the best high-level valuation measures. This is simply a ratio of stock market capitalization to GDP. It makes sense because, over long periods, stocks should track economic growth. Here is a graph by my friend Michael Lebowitz.

This ratio recently surpassed its tech bubble peak around 20 years ago. This means stocks are more expensive relative to GDP than ever seen in the modern era. Could they get still more expensive? Sure. Some stocks could (and almost certainly will) buck the trend. But this shouldn’t reassure anyone who is putting new money into the market or who holds unrealized gains.

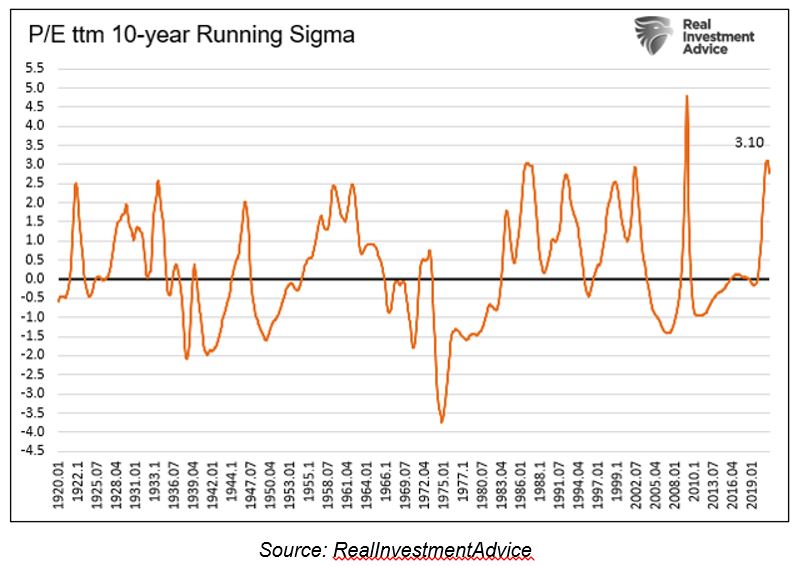

Michael has another interesting chart on price/earnings ratios. He calculated a running sigma, which is the number of standard deviations the current month’s P/E is above/below its ten-year average.

I’ll quote his explanation.

The current reading, of roughly three sigmas, matches or exceeds seven other peaks in the last 100 years. 2009 is the exception. However, that significant overvaluation is a function of earnings collapsing, not excessive prices. In all the cases, the ratio fell to at least zero.

The current sigma is at prior peaks, so any upside appears limited.

If the market reverts to a zero sigma, we should expect 36% losses. Again, a decline to negative readings will compound the losses.

For P/E to simply return to what was “normal” over the last ten years will take a 36% loss. But past bear markets didn’t stop there. Long periods of overvaluation get balanced by subsequent undervaluation. So, it’s entirely reasonable to think the next bear market, whenever it comes, will chop prices in half. That’s not crazy. It is what we should expect.

B-List Triggers

Again, let me stress that the timing is hard. We never know exactly when the sandpile will collapse. We just know it will. The chart above shows the Buffett Indicator has been at worrisome levels for several years. This could continue. But the longer it does, the bigger the sandpile gets, and the bigger the eventual collapse will be.

The ultimate trigger may be something none of us have yet considered—an unforeseeable bolt from the blue—but many plausible triggers are perfectly visible. Some are more plausible than others. I’m going to name several, starting with the “B-list” and then moving to the one I think most likely, and most dangerous, too.

China Crisis

I used to call Japan “a bug in search of a windshield.” Lately, I wonder if it could be China, instead. Or perhaps China is actually the windshield. In any case, China’s sheer size means its problems affect everyone.

The latest China problem is debt-laden property developer Evergrande, which has missed some payments and, as of today, is in default. There is never just one cockroach. While we don’t know the extent, I will bet you a dollar to 47 doughnuts China has dozens of other “Evergrande lite” problems. It’s unclear if the government can help much or even wants to. Xi Jinping is responding to popular unrest with a new “Common Prosperity” theme that looks less business-friendly. Some Chinese commentators I respect seem to believe that the government will take what money the developers still have and use it to finish projects so consumers aren’t hurt.

I would not want to be a bank or funds holding dollar-denominated Chinese debt. They can form all the debt-holder committees they want, but if the CCP is on the other side of the table, you won’t have much leverage. There is no rule of law. There is the CCP and Xi Jinping.

However, the dollar-denominated debt, while seemingly huge, is a drop in the bucket. The rest will be absorbed internally within China, and that is their problem. More likely is a slow-burn crisis.

But the world does have one problem. China is currently the world’s fastest-growing major economy and a critical supplier to most others. If Evergrande depresses construction and business activity while raising the cost of capital, growth in China could slip to a very low level. The real estate and commodities world has grown accustomed to China growing at a compound 6–8%. Any lasting drop would affect businesses worldwide and slow global growth down. This could certainly combine with other forces to generate crisis conditions.

US Political Gridlock

As I write this, the US government is days away from a government shutdown, should the Senate not pass a stopgap spending bill by September 30. Democratic leaders have combined that bill with a debt ceiling suspension the Republicans find unpalatable. It’s not clear if Democrats have the votes on their own side, and some GOP senators could choose to filibuster. So we don’t know what will happen, but it’s another potential fiasco.

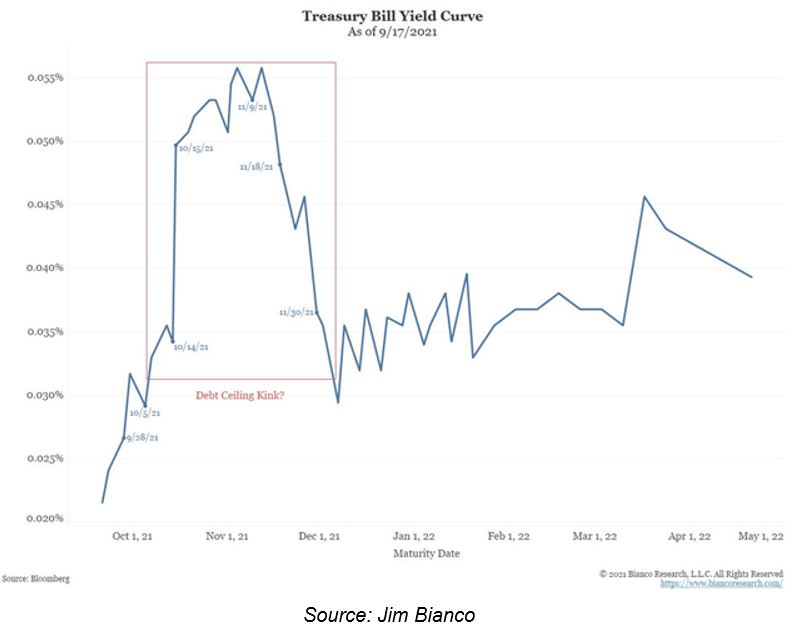

In any case, the US Treasury will hit its legal debt ceiling in the next few weeks unless Congress passes some kind of extension, with potentially serious market effects. As Jim Bianco recently explained on Twitter, the SEC ruled in 2013 that any government security that doesn’t pay on maturity date is in technical default and must be valued at $0. This means money market funds holding T-bills would have to mark down their portfolios if a debt ceiling fight interrupts interest payments. They would “break the buck,” in other words. This risk has created a kink in the yield curve.

However, Jim notes this kink is much smaller than a similar one in the 2013 debt ceiling fight, so traders seem to think the risk is low. We should all hope they are right. And I should point out, after over 40 years of watching this charade, somehow we always seem to increase the debt ceiling. Count me in the group that thinks that risk is low.

US Tax Changes

Congress is also trying to pass a pair of infrastructure bills, one of which has bipartisan support but could fail anyway. They have become bargaining chips in other disputes, both between the two parties and within them. Senator Kirsten Sinema has made it clear she will not vote for any reconciliation bill if the infrastructure bill does not pass. Some House Democrats have made the same declaration.

These aren’t just spending bills, though. They are also tax bills—potentially problematic ones. The House Democratic version includes a provision that would prevent investors from holding non-publicly traded assets like hedge funds and real estate in IRAs. Those who currently have such would get two years to move the assets out of IRA form, at which point, any gains would become taxable.

Where would people get the cash to pay those taxes? Many would have to sell other assets, like stocks. That wouldn’t be good for stock prices. Fortunately, my sources say even many Democrats are against this particular idea, so it (hopefully!) won’t happen.

Other tax changes are quite possible, and even likely, as the negotiations seek “pay-fors” to cover their desired spending. The risk of unintended side effects is high, particularly when the people writing legislation don’t understand how markets work or are being advised by special-interest lobbyists.

The moderate Democrats negotiating with Biden have stated both to him and publicly that they want to know what tax increases Biden needs/wants before they agree to the size of any bill. Reading the tea leaves suggests that corporate taxes and capital gains taxes will rise 4%+, and that income taxes at the highest levels will go back to 39.6%+, Medicare, etc. These would be a drag on the economy, but less so than the original, much-higher proposals—which, (hopefully) are now off the table.

COVID Recession

The pandemic continues to affect economic activity almost everywhere, though the particulars vary. We hear a lot about supply-chain problems. Some of it begins in the exporting countries when virus outbreaks shut down ports and factories. This could continue since vaccinations are proceeding slowly in many of those places—the effects cascade through the economy.

Here in the US, COVID seems to have taken several million people out of the labor force. Some are choosing to retire early, and others are homeschooling their children, changing careers, dealing with “long COVID” disability, etc. There seem to be several million workers who are reluctant to come back to the workforce when COVID is still a significant factor. All of this combines to explain why we have 10 million job openings, increasingly high wages to attract workers, yet few workers are responding. This comes on top of demographic trends that were already reducing the working-age population.

It’s a problem because we need a sufficient number of productive workers to generate GDP growth. I’ve said I expect 1% average growth over the rest of the decade. Note the “average” part. It could and probably will include recessions with below-zero growth. Recession is rarely good for corporate earnings, which is what underpins the present bull market.

Policy Risk

Now, to the main risk. As of a few months ago, quite a few economists expected the September Fed policy meeting would mark the initial tapering of its pandemic stimulus programs. That meeting occurred this week. They still aren’t tapering.

They did throw us a little bone, though. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) statement noted “a moderation in the pace of asset purchases may soon be warranted” if everything goes well… blah, blah, blah. It included all their typical hedge clauses and escape hatches. They promised nothing and may well do nothing at the next meeting, either.

We’ll never know, but I suspect the weak August jobs numbers probably spooked some FOMC members. They have lashed themselves to the “full employment” mast. If that’s not happening, tapering now would generate major credibility questions.

The next FOMC statement will be on November 3. By then, they will have seen the September jobs report and maybe had a peek at October’s (the Fed, like the White House, gets an advance copy of the Friday BLS public releases). If it shows them some plausible path to maximum employment, then maybe they’ll take a first step. I don’t expect it, though. By then, we may also know whether Powell will be reappointed, as seems likely. At that point, Powell may well be willing to begin a taper that might be faster than normal.

Sadly though, I think the Fed has already waited too long. The FOMC members are hoping for some kind of magical return to normal. If inflation pressure keeps growing, it will eventually force their hand. Real rates will become even more negative, and the Fed will have no choice but to begin applying the brakes, possibly harder and faster than the market currently anticipates.

That won’t be pretty, but it’s a real possibility. I consider it the Number 1 risk to both the economy and the stock market. They needed to start tapering last year as soon as it was clear the financial system would hold together. Now they’re boxed in… and we’re all in the box with them.

What Could Go Right?

Sentiment drives markets, at least in the short term, which presents us with a conundrum. Markets are near their all-time highs, yet sentiment is weakening. Let’s quote from my friend Philippa Dunne of TLR Analytics.

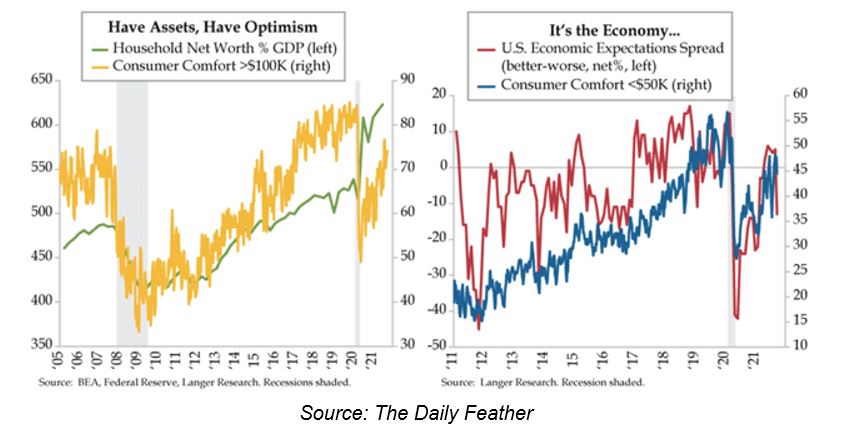

This morning, Langer Research Associates reported that those who believe the economy is improving fell 11 percentage points, to 27%, between mid-August and mid-September, the sharpest dive in 13 years. Those who believe the economy is getting worse rose by 7pps to 40%. Since 1985, the spread between brightening and darkening outlooks has averaged -17 points, so the sudden September decline is the bigger concern. Outlooks among households making less than $50,000 fell by 16 points, among higher earners by 5 points, among Democrats by 21 points, and among Republicans by 13 points.

LRA highlights that their current-sentiment gauges have also fallen over the last three weeks from what they are calling their pandemic peak, and unevenly. Rating the national economy, the largest losses were among Republicans, 9.7pps, households making less than $50,000, 9.2pps, with losses of 8.7pps among Southerners, and 6.3pps among women. Personal finances and buying climate are both off by about 2pps.

In his morning missive, David Kotok flagged the Conference Board’s 18-point jump from 24% in June to 42% August, in those ranking risk of contracting Covid personally among their greatest concerns about returning to work, with women and millennials more concerned about catching Covid themselves and about spreading it to their families, another rising share.

Our friend Danielle DiMartino Booth of Quill Intelligence put that data into charts:

That data and charts reflect the view outlined above of what could go wrong. But what could go right? What could change that sentiment?

Last week my doctor, Mike Roizen, told me COVID models, developed by scientists who advise CDC, that are finally beginning to improve. One scenario suggests infections will fall 80% or even more by March.

Getting past this pandemic could create a huge turnaround in the country’s mood. Workers would feel far more comfortable coming back to work, you could find millions of people—especially in the lower-income ranges—finding jobs, the unemployment number would drop significantly—much closer to 4%—the economy would improve, and sentiment would potentially come roaring back.

The Fed would have room to finish the taper faster and actually begin raising rates to something that looks like “normal.” In another six months, more supply chain problems will be solved (with the exception of computer chips), and the economy will resume functioning normally. Business travel will begin to pick up, though maybe never to the prior level since we now know how to have events online. Those of us who speak for a living may actually find ourselves in front of crowds again.

Homebuilders could finally catch up with the demand from first-time homebuyers. Businesses would see new opportunities and make capital investments again. You know, like normal.

Maybe we even get an honest-to-God 10%+ correction in the markets, creating a buying opportunity as that sentiment begins to build. The Cowboys might even win the Super Bowl. (Okay, maybe not that last one, but we can dream.)

Optimistic? Yes, but appropriately and cautiously optimistic. We keep our eyes on the COVID statistics. We pay attention to the supply chains. We watch the sausage factory in Washington DC hopefully not do too much damage to the tax structures and create too many job-killing regulations.

But a rally from here because of the relief of COVID being behind us is not out of the question. I can think of other things that can go right. New technologies will be amazingly powerful drivers of not just wealth but jobs and opportunities. New medicines and drugs. New ways to do things cheaper.

The contrast between what could go right and what could go wrong has hardly ever been starker. I still think we are in a market where I would rather diversify among trading strategies rather than buy-and-hold index funds, which reflects my cautious optimism. I am in the markets, but there is a hedge. And, of course, I still look for those truly transformational technological innovations. It is actually a wonderful time to be alive.